Anglo-Indian Silver by Wynyard Wilkinson

Wynyard Wilkinson is a specialist in antique British and Colonial silver. He has lectured and published extensively on silver made by British artisans in all corners of the former Empire, with particular expertise in India. Find out more here.

Our forthcoming auction of Fine Jewellery, Silver and Luxury Accessories on Thursday 7 July, includes a lovely private collection of Anglo-Indian silver (Lots 50-93). Here, Wynyard offers his expertise on the subject, looking at examples from the collection.

Of all art forms traditionally associated with India, silver work is perhaps the least well recognised. It is for this reason that I have devoted much of my life to the study of these rich and varied objects and their makers. In fact, when I began my study of silver produced in India for Europeans, most pieces were mistakenly attributed to Scottish origins. In my youthful enthusiasm to get it right, I had no idea that publishing my study, accurately identifying an entire body of silver wares as having been produced in India for the European expatriate community there, would chafe the powers that were in the silver dealing and collecting world of 1971; but this is an art form whose time is now. Both in their ‘Colonial’ guise as well as in their ‘indigenous’ aspect, these are pieces which offer Westerners as well as those whose lineage reaches to the sub-continent, a new window into the staggering artistic contributions of Indian artisans. Representing as it does a confluence of tastes and styles that its at once familiar and iconoclastic makes this a lush subject for studying and collecting.

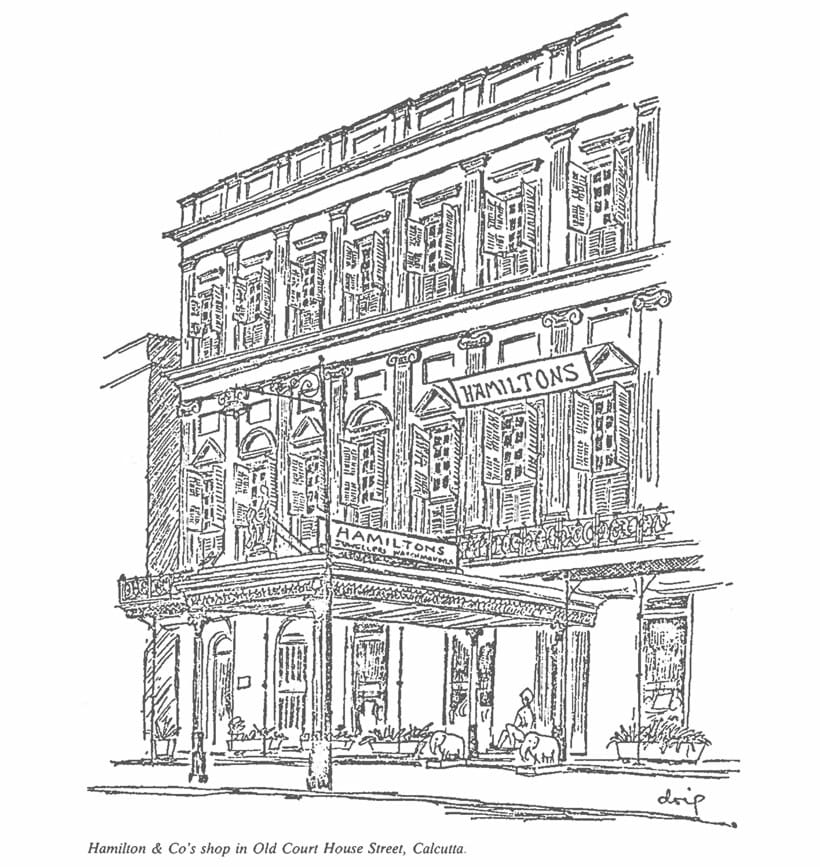

There are two basic categories of Indian silver made during the period of European influence, which lasted from roughly 1750-1950. The first of these is silver of English form and design. Such pieces were produced under the auspices of European jewellery houses which maintained premises in the three Presidency towns: Calcutta (now Kolkata), Madras (now Chennai), and Bombay, (now Mumbai), as a means of attracting retail customers. Although the primary source of revenue for these firms was the transferring of money to Europe through the movement of precious stones, the production of traditional silver objects for local European consumers became an increasingly significant part of their business.

The second category is silver which is European in form and function, but which features distinctly Indian decorative embellishment. Familiar items such as tea sets, salts, peppers, cream and water jugs, etc. adorned with exotic local decoration were produced to satisfy the expatriate community’s demand for items that looked (to a European) the way Indian silver should. These pieces are also significant historically because they represent an effort on behalf of concerned Europeans (like Lockwood Kipling, father of Rudyard) as well as local hierarchies to establish viable crafts when traditional ‘indigenous’ crafts (such as weaponry) were in jeopardy. The Prince of Wales’s (later Edward VII) tour of India in 1876 provided an opportunity for each princely state to produce a seminal example of its regional style for presentation. Those few states without such a local idiom quickly developed one for the occasion and the results are silver objects ranging from stately elegance to comic quaintness.

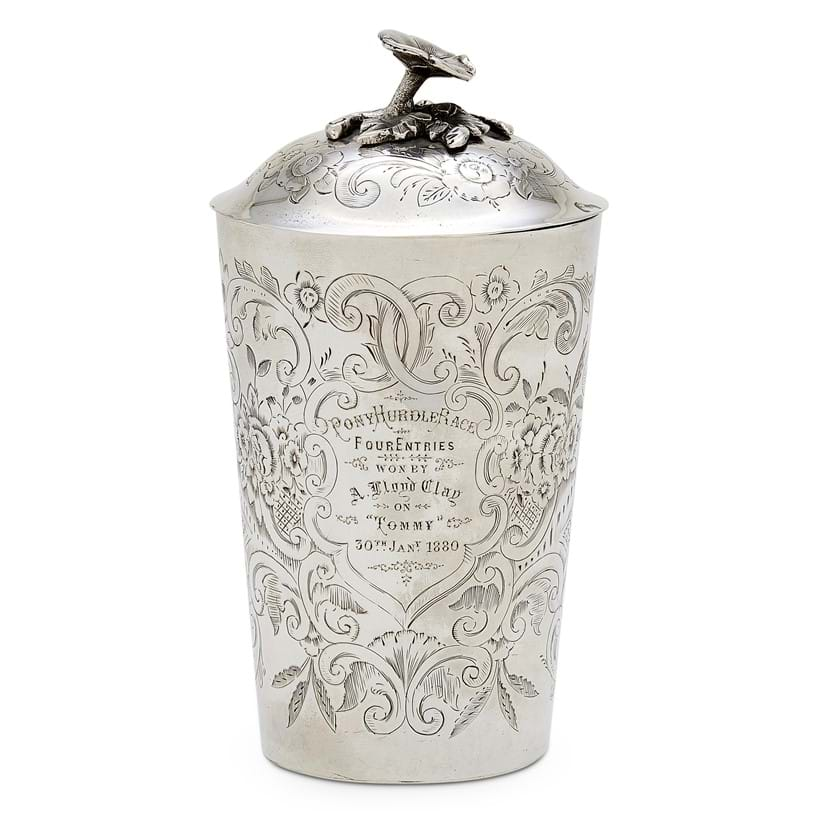

In addition to these two basic categories of silver are pieces in the English taste, but which were designed to fulfil the specific requirements of Anglo-Indian social life. These items include milk and butter coolers (Lot 59), obviously necessary in the intense heat; covered goblets and beakers (Lots 86 & 91), which kept insects from spoiling one’s libation; rice bowls; saucepans which transform themselves into serving dishes by means of detachable horn handles (Lot 55); and salts and peppers in a form that fits snugly into a servant’s sash, as everyone travelled not only with his own retainers, but his own personal seasoning as well. As a certain Mrs. Fay observed in her Letters from India of 1780,

"People here are mighty fond of grills and stews which they season themselves, and generally make very hot. The Burdwan stew takes a deal of time; it is composed of everything at table, fish, flesh, and fowl…many suppose that unless prepared in a silver saucepan it cannot be good."

Such silver objects are my personal favourites as not only do they represent the complete synthesis of two divergent traditions, but they are also highly accessible and useful today. That they are the surviving artefact of a vanished culture only adds to their allure.

If Indian silver gained instant cachet in England when the collection of pieces presented to the Prince of Wales toured the country in 1878-79, international enthusiasm was guaranteed when these treasures were exhibited at the Paris Exposition of 1878, an event attended by some 16 million people from all over the world, including William Morris, John Millais, and Edward Burne-Jones. Suddenly the Indian style was in demand in places as far away as America, where Tiffany produced silver objects in the “East Indian” taste. London shops struggled to keep up with demand for Indian style goods. Liberty’s included Indian silver in their Christmas catalogue, and Elkington & Co. produced exact copies of Indian style pieces.

There were five major and several minor centres of silver manufacture in India for this ‘hybrid’ silver with Indian style decoration. Kashmir, a tourist centre with beautiful lakes and exquisite Moghul palaces and gardens, adapted Moghul motifs for its silver from its famous buildings and fabrics. Kolkata’s silver style features scenes from quotidian life in its surrounding villages. Chennai silver is characterised by scenes from Hindu mythology and representations of deities. Silver from Lucknow, another famous tourist destination, features either a fine decoration derived from coriander flowers or scenes depicting the thrill of the hunt, with animals obscured in forests of palm trees. Kutchi silver, probably the most commercially successful on an international scale, is encrusted with elegant scrolling foliage and often includes carefully articulated animals and birds (see Lot 91). The magnificent silver of Kutch owes much of its popularity to one virtuoso silversmith, Oomersi Mawji, whose grasp of the symbiosis of form and decoration, together with his superlative technique, made his work internationally famous and enabled other Kutchi silversmiths to successfully market their wares.

View page turning catalogue

Auction Details

Thursday 7 July | 10.30am BST

Donnington Priory, Newbury, Berkshire RG14 2JE

Browse the auction

Sign up to email alerts

VIEWING:

- Viewing in London (selected highlights):

- Monday 20 June: 10am-5pm

- Tuesday 21 June: 10am-5pm

- Viewing in Newbury (full sale):

- Sunday 3 July: 10am-2pm

- Monday 4 July: 10am-5pm

- Tuesday 5 July: 10am-5pm

- Wednesday 6 July: 10am-5pm

- Day of sale: no viewing

- Remote Viewing Service | Available from Sunday 3 July